I had accidently landed on this page via twitter and found this story interesting. The interpretation of Duryodhna’s flashing of his left thigh is to the point. In Indian patriarchal society, man flashing thigh is similar to exhibition of phallus and writer of Mahabharata also wrote for the same reason.

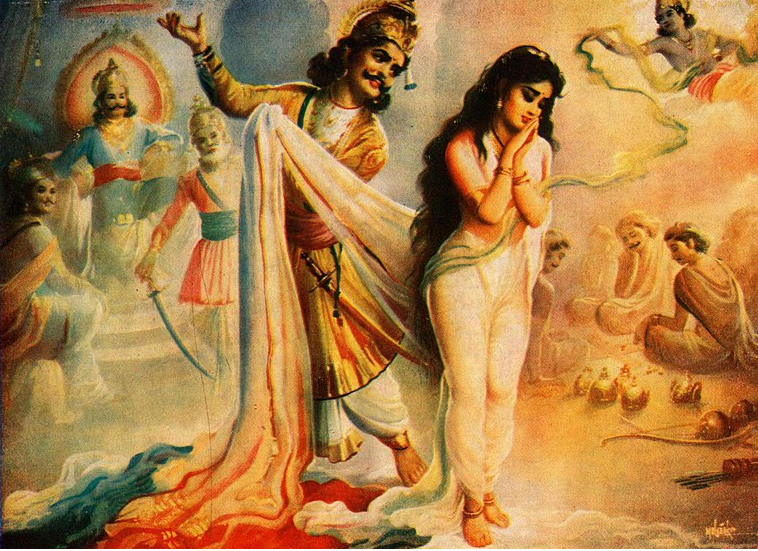

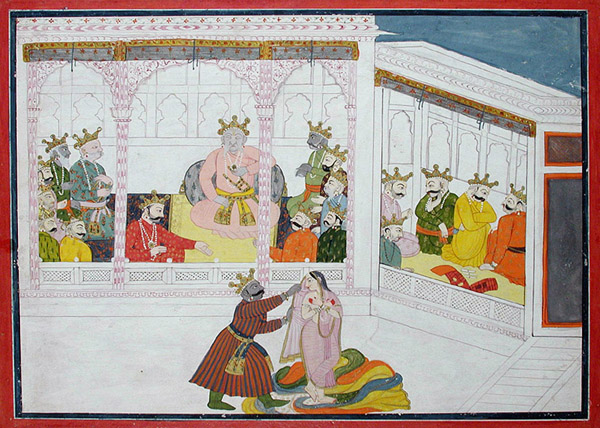

French feminist Hélène Cixous has written that a “feminine text cannot fail to be more than subversive,” especially one trying to recast a female archetype. Dopdi is an illiterate Santal, a tribal rebel involved in the clash between the government’s army and West Bengal’s Naxalites in the 1970s. She is eventually captured by the army officer Senanayak, tortured and gang raped. Devi suggests the act of rape through the image of “active pistons of flesh” rising and falling over the “spread-eagled still body.” Similar phallic imagery is employed in the epic when the eldest of her five husbands, Yudhisthira, stakes and loses Draupadi in the infamous game of dice, and the opposing Kaurava clan wants to claim her as their own. At the climax of the disrobing scene in the Kaurava’s assembly hall, or sabha, when Dushasana starts pulling her sari in an attempt to strip and embarrass her in public, Duryodhana flashes his left thigh at Draupadi – the “stem of the plantain tree… the trunk of an elephant… endued with the strength of thunder.” Indologist Sally J Sutherland believes that the expression ‘left thigh’, savyam urum, is a euphemism for male genitalia. In both cases, power is implied and displayed by the symbol of the phallus.

In the epic, Draupadi’s ‘modesty’ is saved by the divine help of Krishna – her sari turns endless and unstrippable. But the events in Devi’s story take an unprecedented turn. Dopdi tears her blood-stained cloth with her teeth and walks naked towards Senanayak: “What’s the use of clothes? You can strip me, but how can you clothe me again? Are you a man?… Come on, counter me”. In an act resembling contemporary performance art, she redefines her position as unthreatenable, and herself as – in the words of feminist scholar Sharon Marcus – “neither already raped nor inherently rapable”.

Devi’s ‘Draupadi’ is an attempt to lay bare the harsh political landscapes inhabited by the tribal or autochthonous peoples who almost always bear the brunt of forced development. The Mahabharata, on the other hand, is a conflicting and collaged narrative with easily discernable seams and stiches where interpolations were fitted in. Each of these digressions was carefully chosen to prove or blur a point, depending on the agendas of a particular time and space. According to some scholars, the Mahabharata can be read as a record that both maps and justifies the imperialistic tendencies of the Pandavas, and their consequent claiming of the forests: aided by Krishna, Arjuna burnt the Khandhava forest to build their capital, Indraprastha.

The various tribal people, who lived on the territory, were either killed or fled. Moreover, there is a distinct correspondence between Devi’s description of the official treatment of governmental violence against the tribals (“How many killed in six years’ confrontation? The answer is silence”) and the atmosphere in the sabha when Draupadi’s pleads before the assembly (“but the kings present didn’t say a word good or ill”). The two impenetrable walls of silence that Draupadi faces are made of the same stuff.